You can’t seem to get through a succession planning discussion without the topic of “executive presence” coming up – usually in the context of someone who doesn’t have it and really needs it to move up. It’s always a fuzzy discussion – no one can really articulate what EP is. In hopes of describing this seemingly indescribable “je ne sais quoi” of leadership, people point to everything from confidence and emotional

The more I’ve researched the topic of EP, the more convinced I am that we’re looking at EP in the wrong way – like we’re trying to solve a calculus problem using basic algebra. Here’s the issue. Most of the leadership thinking out there today is very much focused on developing the behaviors and attitudes of the individual. We posit that when we stick the new-and-improved individual back in the workplace, everything gets better. The reason this mindset doesn’t work for EP is that EP is not a set of skills, it’s an effect – the impact that the individual has on the room, the team, the organization. EP is a dynamic of an organizational system. The leader and the followers together create the effect that we end up tagging as Executive Presence.

So to unpack the concept of EP to find something actionable, we need to turn away from the traditional leadership development approaches and look to systems theory. OK, so this might seem a bit daunting. In the last few decades, psychologists, mathematicians, anthropologists and behavioral scientists have all drilled into how to make organizations work better by viewing the world of work as a system. White papers on everything from chaos theory to the organizing behaviors of chimpanzees abound.

In sifting through it all, the most relevant source of insight on leadership in a system comes from an unexpected place - a family therapist by the name of Murray Bowen, who went on to develop Bowen Family System Theory. He later founded the Bowen Center for the Study of Family at Georgetown University. Bowen’s clinical research and experience in counseling families led him to a controversial conclusion – that, in humans, the “emotional unit” is not the individual, it’s the family. Groups of people, starting with the family, act as a system emotionally. This means that the emotional climate and basic functioning of any group of people who live or work together is the result of the interrelated roles played by the members of the group – always reacting and adapting to each other.

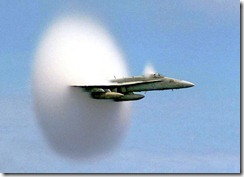

So hang in there with me while I connect this back to executive presence. Bowen’s work on family systems has become the basis for some groundbreaking work in the area of leadership and organizational performance. The basic premise is that every workgroup is managing a certain level of chronic anxiety – a level that appears to be increasing as the world of work becomes less stable and predictable. And each individual brings a different level of “functioning” to the group – the ability to stay engaged with people in a positive way, while not getting sucked into the emotional mess that results from the anxiety. Bowen refers to this level of functioning as “differentiation,” and it’s at the heart of executive presence.

In short, the higher the level of differentiation a leader possesses, the more able he or she is to reduce the anxiety of a group while guiding clear-headed decisions. People feel less anxious and are drawn to follow highly differentiated people, which is why those people tend to gravitate to leadership roles. These people have Executive Presence. Highly differentiated leaders can also handle higher levels of stress and unpredictability, which makes them more resilient

For a leader, improving differentiation, understanding people system dynamics, and even learning to read the shifting level of anxiety in an organization is hard work. And much of it requires throwing out many of our long-held assumptions about organizations and leadership. There are some great books out there for those willing to learn about it and do the work. Roberta Gilbert has written several, including The Eight Concepts of Bowen Theory, Extraordinary Leadership and The Cornerstone Concept – a trilogy written to support training of clergy leaders of all faiths, but extremely useful in the broader leadership context. Other notable books are Resilient Leadership, an engaging, parable-style book by Duggan and Myer, and Leading a Business in Anxious Times by Fox and Baker. Each has done a reasonably good job of steering away from clinical psychology terms to make the topic more practical and accessible.

This work based on Bowen Theory also demystifies other leadership dilemmas – like why a successful leader of one team can hit a wall when given a new team, or even why workgroups can have cultural or attitudinal issues that persist for years after the leader and key team members have moved on. So an exploration of Bowen Theory for leaders may force us to re-examine not only what executive presence is, but how leadership and organizations actually work.

Yes, it appears that we could be on our way to defining the X-Factor in leadership and executive presence, and I think we’ll all be hearing a lot more about this in the next few years.